Two dimensions of AI Agency

When I joined SpeechWorks in 1999 after several years spent trying to advance speech recognition, statistical natural language understanding, and dialogue systems from a research perspective at AT&T Bell Labs, I quickly encountered a reality check: what I had learned in the lab, my algorithmic knowledge, was necessary, but not sufficient.

SpeechWorks was one of the very first companies (the other, at the time, being Nuance) that seriously attempted to turn speech recognition and natural language understanding, two still-unreliable technologies developed in the research labs, into commercial products for customer care. There I learned that success depended not only on algorithms, but on how those algorithms behaved with real customers on the other side of a telephone line. And the customers were not always thrilled, to say the least, to talk to a machine rather than a human agent. Remember, that was the early 2000s, and speech recognition was not really working well.

That’s where I was first exposed to what we would today call conversation designers; back then, they were known as VUI, or Voice User Interface designers. Watching them work was eye-opening. I learned how careful dialogue structure, wording, pacing, and error handling, designed with a deep understanding of human behavior, could turn a non-working system into a working one. That was a science rooted in the knowledge, or the art, of understanding human behavior. In fact it was at SpeechWorks that I first heard leaders talk about “The Art and Science of Speech.” The phrase stuck with me, since it captured a simple but profound truth: when humans are involved, algorithmic correctness alone is not enough. Those insights were reinforced later, in 2005, when I joined SpeechCycle. There, effective VUI design once again proved fundamental to the success of the voice-based automated troubleshooting systems we brought into production.

Around that time I read The Media Equation by Byron Reeves and Clifford Nass, two Stanford communication researchers. Their claim, supported by experimental evidence, was that people instinctively treat computers, media, and interactive technologies as social actors, applying to them the same rules and expectations they use with other humans. One everyday example of this, surprisingly common at the time in automated telephone customer care, was customers saying “goodbye” before hanging up at the end of an interaction, fully aware that they were talking to a computer rather than a human agent.

At the time, this behavior struck me as an interesting curiosity, an instinctive reflex, perhaps, revealing more about human psychology than about the technology itself. I saw it as a subtle signal of how easily social expectations spill over into our interactions with machines. But it was still something I observed at a distance. That changed later, when I joined the robotics company known as Jibo. At Jibo we built and shipped the first consumer social robot for the family.

Jibo was not anthropomorphic in the traditional sense, yet it deliberately conveyed a sense of warmth and approachability. Through smooth, expressive motion driven by three motors, a carefully designed adolescent-like voice, and the ability to recognize faces and voices, Jibo behaved in ways that felt socially responsive. Its animations, timing, and humor were all designed to invite engagement rather than simply deliver functionality.

The effect was difficult to ignore. Jibo demonstrated that people do not just use technology; they can form genuine bonds with it. Its design was explicitly centered on fostering an emotional relationship, layered on top of practical capabilities. As a result, early Jibo adopters, many of them technology enthusiasts, began to treat the robot as a member of the household. They addressed it as a presence rather than a device, expressed affection toward it, and when Jibo was gone, experienced something close to loss.

This wasn’t a design trick or a marketing illusion. It was a deeply human response to a system deliberately built for relationships layered on top of transactions, a system that persisted over time, responded socially, shared physical and temporal space, and acknowledged the user. Jibo’s design drew directly from social robotics research led by Cynthia Breazeal at MIT, as well as from principles of character animation. The result was not merely a device that performed tasks, but one that conveyed presence and continuity. Because of that, Jibo wasn’t just executing functions. It was participating in an ongoing relationship with its users.

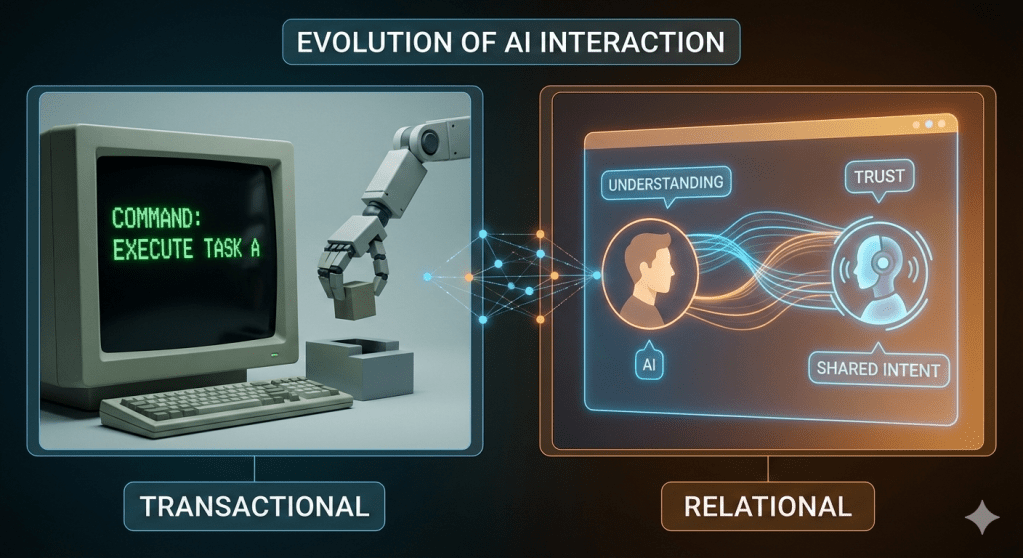

That experience left a deep mark on me. And today, I’m convinced that we need an evolution of AI, from purely transactional systems to relational ones. Not because relationships are fashionable, but because they are how humans cope with uncertainty, ambiguity, and imperfect communication.

That evolution is not accidental. As we will see, it is deeply rooted in human evolution itself.

Conversation Is Not Just Natural Language

Before moving into a discussion of the role of conversation in the evolution of relational intelligence in humans, it is useful to clarify, for a general audience, some of the terms I use throughout this blog.

When we describe an AI system as conversational, it is tempting to equate that simply with the use of natural language. But conversation is not defined by fluency or grammar alone.

Command-based systems, such as search engines or early virtual assistants, assume that users know exactly what they want and can state it upfront. They are well suited for executing clearly specified requests. Typical examples include queries like “flights from Boston to San Francisco,” “set an alarm for 7 a.m.,” or “play jazz music.” In each case, the goal is already formed, and success depends on accurate execution of a well-defined instruction.

Conversation serves a different function. Humans rely on conversation when goals are unclear, evolving, or only partially formed. Through dialogue, we clarify intent, adjust priorities, and resolve misunderstandings. A conversational interaction might begin with something like, “I’m thinking about visiting California sometime in the spring,” and then evolve through questions, suggestions, and revisions until a concrete plan emerges. Conversation is not just a way to issue instructions, but a mechanism for discovering what the right instruction should be.

This is also why elements that may appear secondary, such as small talk or brief stories, play a role. A simple exchange like “How’s your day going?” or a short anecdote such as “Last time I took a morning flight, the airport was much less crowded” does not directly advance the task. Instead, these moments help establish context, signal expectations, and reduce uncertainty. They create a shared conversational space in which more goal-directed interaction can take place.

In short, commands are effective when goals are known and precise. Conversation is how humans navigate uncertainty and build shared understanding.

Why Relational Intelligence Evolved in Humans, and Why Conversation Matters

Keeping this distinction in mind gradually changed how I thought about conversation. If conversation were simply a more natural way of issuing commands, its role would indeed be limited to interface design. Over time, however, it became clear to me that conversation plays a deeper role. It is how humans deal with uncertainty when goals are unclear, evolving, or only partially formed. From an evolutionary perspective, conversation is not something layered on top of intelligence; it is one of the processes through which relational intelligence emerged, enabling collaboration and, ultimately, the formation of human societies.

While working on the Google Assistant, I began to think more deeply about why conversation matters and why it is fundamentally different from a simple command language, like those used in search engines and in early virtual assistants such as Siri, Alexa, and the Google Assistant. The question was not about usability alone. It was about why humans naturally gravitate toward conversation when interacting with other agents, rather than issuing precise commands.

As I started reading more about the social evolution of humans, a clearer picture emerged. Conversation is not just a convenient interface; it is one of the primary mechanisms through which humans form relationships. And relationships, in turn, are what enable sustained collaboration, allowing groups to pursue goals that no individual could realistically achieve alone. Seen in this light, conversation is not an alternative to command languages. It is the evolutionary foundation for cooperation.

From an evolutionary perspective, relational intelligence is not a luxury; it is a survival mechanism. Humans did not evolve in environments where goals were clear and instructions precise. Early human life was shaped by uncertainty: uncertain environments, uncertain outcomes, and, most importantly, uncertain intentions and behaviors of other humans.

An additional and often overlooked role of conversation and relational intelligence is the negotiation of meaning and the gradual construction of a more objective representation of reality. An individual, acting alone, inevitably interprets the world through a subjective lens shaped by personal experience and limited information. Within a group, however, conversation allows multiple perspectives to be compared, challenged, and refined. Through this process, groups can converge toward a shared understanding that is more robust than any single viewpoint. Relational intelligence, and the capacity to converse, are therefore central not only to cooperation, but also to the collective effort of making sense of the world.

Purely transactional intelligence, in other words the mere execution of commands, works well for tools, but it breaks down in social settings. As anthropologists like E. O. Wilson described in The Social Conquest of Earth, human success depended on long-term cooperation: coordinated hunting, food sharing, alliance formation, and conflict resolution. These activities could not be reduced to simple transactions.

Relational intelligence emerged to solve this problem. As Michael Tomasello argues in The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition, humans developed the ability to form shared intentions and align goals through interaction. Later, higher-order theory of mind, in other words reasoning about what others think about us, and what others think about what others think about us (higher order theories of mind), further amplified this capacity. As Blaise Agüera y Arcas explains in What Is Intelligence?, this recursive social modeling required larger, more complex brains, but enabled stable cooperation and cumulative culture.

Conversation is thus the mechanism through which this intelligence operates. Conversation, rather than simple one-shot command-and-control interactions typical of many modern virtual agents, is not only about information exchange. It is how humans negotiate intent, explore ambiguity, test alignment, and repair misunderstandings.

As noted above, we should also not underestimate the importance of small talk and brief stories in establishing and maintaining a collaborative relationship. Humans are often fuzzy about how they want something done, even when they believe what they want is crystal clear. Conversation evolved precisely to manage that fuzziness.

Seen this way, relational intelligence is not just about empathy or politeness. It is about keeping cooperation alive in the presence of uncertainty. And it evolved alongside, never in place of, transactional execution, which remained constrained by physical reality and social norms.

This evolutionary lesson matters for AI. As AI systems move into human environments, and their conversational capabilities evolve to human-like levels, they face the same ambiguity that shaped human intelligence. Purely transactional systems struggle there. Relational intelligence, properly bounded, is not optional, it is the mechanism to achieve usefulness. Humans learned this lesson over millennia. AI systems need to learn that much faster.

The Need for Relational Intelligence

Let’s go back to AI agents. As AI systems increasingly interact with humans over extended time horizons, they begin to face challenges that are strikingly similar to those encountered by early humans living in complex social groups.

At a high level, AI agents interact with two fundamentally different kinds of external entities: tools and humans. Tools include databases, Web search engines, APIs, and software applications. Humans include users, collaborators, supervisors, and decision-makers. While these interactions are often treated uniformly in system design, they are radically different in nature.

Interactions with tools are, by design, transactional. Tools expose well-specified interfaces and APIs. When an AI agent issues a request that is syntactically correct and semantically well-formed, the outcome is highly predictable. Errors, when they occur, are usually explicit and local: an invalid parameter, a missing field, an authorization failure. The assumptions on both sides of the interaction are clear and stable.

This predictability disappears when the interacting entity is human. Human interaction is inherently underspecified and dynamic. AI agents frequently need to ask for additional information, request clarification, repair misunderstandings, or refine goals over multiple turns of interaction. Even when an AI agent formulates a clear and reasonable question, the human on the receiving end may misunderstand it, interpret it differently than intended, or be unable to provide a precise answer.

More fundamentally, humans often do not have a fully articulated goal at the outset. They may have a more or less clear high-level intention, but not a precise definition of what they want or how they want to achieve it. Rather than declaring intent upfront, they often discover it through interaction. Goals can shift as new information becomes available, preferences can evolve, and priorities can change midstream.

A familiar example is planning a trip using Google Flights. One might start with a rough idea, say, a destination and approximate dates. Once the initial results appear, however, the process becomes iterative. Seeing prices may prompt a change in travel dates; long layovers may be traded off against lower fares; departure times may become more important than cost, or vice versa. What began as a vague intention gradually turns into a concrete plan through successive refinements. This kind of goal formation is not an exception. It is how humans routinely operate, and it is precisely the kind of interaction that purely transactional systems struggle to support.

In addition, communication errors are inevitable. Humans and AI agents operate with different assumptions, background knowledge, and mental models of the task at hand. What seems obvious to one may be unclear to the other. Ambiguity, partial information, and misalignment are not edge cases, they are the norm.

This asymmetry between tool interaction and human interaction is critical. While pure transactional mechanisms are sufficient for interacting with tools, they are inadequate for interacting with humans over time. Sustained human–AI interaction requires mechanisms for managing uncertainty, negotiating meaning, adapting to evolving preferences, and recovering gracefully from misunderstandings. In other words, as AI agents move from operating in well-defined technical environments to participating in human-centered ones, relational intelligence becomes essential, not optional.

Looking Ahead: What It Means to Make AI Relational

If relational intelligence played such a central role in human evolution, it is natural to ask what it means, in practical terms, to bring similar capabilities into AI systems.

Making AI relational does not mean making it autonomous, emotional, or human-like in a superficial sense. Rather, it means acknowledging that sustained interaction with humans inevitably involves uncertainty: uncertainty about intent, about preferences, about context, and about how goals evolve over time. Relational Intelligence is fundamentally about managing that uncertainty jointly with the user.

At the same time, relational intelligence should not be seen as a replacement for transactional intelligence. The two should be understood as coexisting, parallel dimensions of intelligent systems. Transactional intelligence is what enables systems to execute actions accurately, consistently, and predictably. It is the foundation on which trust is built. Users learn to rely on a system because it does what it is supposed to do, every time, within well-defined boundaries.

Relational intelligence plays a different but complementary role. It shapes how users interact with the system over time, how easily they can express vague or evolving goals, how misunderstandings are handled, and how friction accumulates, or is avoided, across repeated interactions. While trust derives primarily from consistent and accurate transactional behavior, usability emerges from the relational dimension: from the system’s ability to engage in conversation, adapt to context, and remain coherent as situations change.

From a technology perspective, this suggests a shift in focus. Intent should not be treated as a static variable to be inferred once, but as something that often emerges and stabilizes through interaction. Clarification, negotiation, and repair should not be considered exceptional cases, but core mechanisms of intelligent behavior. Similarly, long-term interaction, memory, and adaptation over extended time horizons deserve more attention than they traditionally receive.

It also suggests that evaluation needs to go beyond one-shot task completion. Measures of success should reflect whether systems remain useful over time, whether they adapt appropriately as preferences change, and whether they recover gracefully from misunderstandings rather than accumulating friction.

On the technology side, this perspective points toward architectures that keep transactional and relational concerns distinct but tightly coupled. Conversational and relational capabilities can help interpret intent, manage ambiguity, and maintain continuity, while execution remains explicit, constrained, and accountable. In this sense, relational intelligence enhances usability without undermining reliability.

Perhaps most importantly, this framing reinforces the idea that conversation is not merely an interface choice. Conversation is the mechanism through which humans align goals, negotiate meaning, and build shared understanding in the presence of imperfect information. As AI systems increasingly operate in human-centered environments, they inherit these same conditions.

Human evolution offers a useful reminder. Relational intelligence did not emerge to make humans more autonomous or efficient in isolation. It emerged alongside transactional competence, enabling cooperation under uncertainty. If AI systems are to become genuinely useful partners over time, they will need to embody the same balance. That balance is not a design preference. It is a consequence of the complexity of human-machine interactons.

Relational Intelligence and Large Language Models

With the advent of large language models and the recognition that their emergent capabilities approach certain forms of reasoning, and even limited aspects of common sense, an important question has emerged: do these massively pretrained systems, exposed only to text, demonstrate any form of relational intelligence?

Early scientific work addressing this question is beginning to appear. One example is Evaluating Large Language Models in Theory of Mind Tasks by Michal Kosinski, which reports LLM performance on false-belief tasks analogous to the classic Sally-Anne experiment in developmental psychology. Kosinski’s results suggest that as language models scale from early systems such as GPT-1 to more recent ones like GPT-4, their performance improves substantially, reaching levels comparable to, and in some cases exceeding, those typically observed in children around six years of age.

Other recent studies explore similar questions from complementary perspectives. For instance, in Theory of Mind in Large Language Models: Assessment and Enhancement by Ruirui Chen the authors examine existing benchmarks used to evaluate ToM in LLMs, mostly story-based tasks that test whether models can infer beliefs, desires, and intentions of characters. They also survey various strategies proposed to improve these abilities in LLMs and point out promising directions for future research to make models better at interpreting and responding to human mental states in more realistic and diverse interactions.

A related research direction focuses less on isolated reasoning tasks and more on cooperation and coordination under uncertainty. Work in Cooperative AI, such as Open Problems in Cooperative AI by Allan Dafoe and Foundations of Cooperative AI by Vincent Conitzer and colleagues, emphasizes shared goals, negotiation, and alignment across agents, framing relational intelligence as something that emerges through interaction rather than being computed in a single step.

More broadly, there is growing recognition that conversational AI cannot be evaluated solely through one-shot task success. Long-horizon interaction, memory, preference drift, and user trust increasingly point toward evaluation criteria that better capture relational qualities, including coherence over time, recovery from misunderstandings, and adaptation as shared understanding evolves.

While this overview is not exhaustive and focuses primarily on academic research, it reflects a growing scientific interest in relational intelligence. What remains open is how to translate these insights into practical systems that balance relational flexibility with transactional reliability over extended interaction

What remains open is how to translate these insights into practical systems that balance relational flexibility with transactional reliability over extended interaction.

Conclusion

Transactional intelligence gives AI systems their reliability. Relational intelligence gives them their usability. One without the other is insufficient for sustained interaction with humans. Human evolution suggests that intelligence did not scale by replacing precise action with social reasoning, but by developing both in parallel. As AI systems move into increasingly human-centered environments, they face the same reality: uncertainty is not an edge case, but the norm.

The challenge ahead is not to make AI more autonomous, but to make it more capable of participating in interaction over time, accurately, consistently, and with an awareness of how meaning, intent, and trust emerge through conversation. That balance may ultimately determine whether AI systems remain tools we tolerate, or partners we can actually work with.

Leave a comment